What you need to know about extensometers to get us to talk the same language.

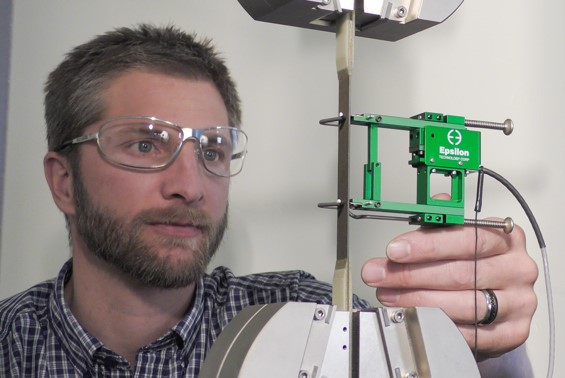

What is an extensometer, and why are they used?

When used for materials testing, extensometers are used to accurately measure material properties that are critical for a vast range of engineering designs – aircraft, energy systems, medical devices, automobiles, and civil structures, to name a few.

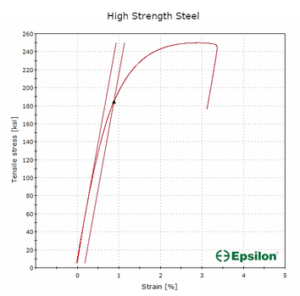

Extensometers measure the extension, compression, or shear deformation of a material sample when force is applied in a testing machine. They are often used to measure the test piece’s strain, which is calculated by dividing the change in the test specimen’s length by its original gauge length. Key properties such as elastic modulus, offset yield, total elongation, and complete stress-strain curves can be measured when using an extensometer.

Extensometers measure strain (or displacement) directly on the test specimen. As a result, they provide far more accurate and repeatable measurements than measurements based on the motion of the testing machine’s crosshead, which would include errors caused by deflections in the testing machine’s load cell and drive components. They come in a great variety of shapes, sizes, measuring capacities, and temperature ratings, and they may contact the specimen directly or make measurements optically without contacting the specimen. Extensometers are reusable and last for years, and they are very cost-effective compared to adhesively bonded strain gages or digital imaging measurements.

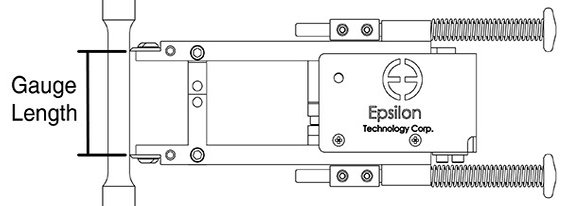

What is Gauge Length?

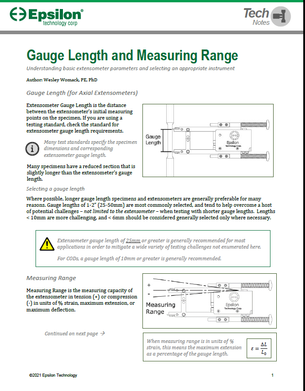

An extensometer’s Gauge Length is the distance between the extensometer’s initial measuring points on the test specimen.

If you are using a testing standard, such as an ISO or ASTM standard, check the standard for extensometer gauge length requirements. Many test standards specify the specimen dimensions and a matching extensometer gauge length.

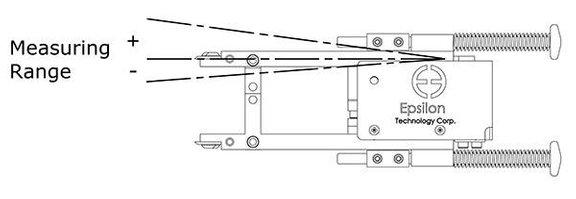

What is Measuring Range?

An extensometer’s Measuring Range is the extensometer’s measuring capacity in tension (+) or compression (-) in units of % strain, maximum extension, or maximum deflection. When the measuring range is specified in units of % strain, this refers to the maximum extension as a percentage of the initial gauge length. Maximum extension, displacement, or deflection will be in length units such as millimeters.

When determining the measuring range required for your application, estimate the maximum strain or extension values you will need to measure, such as the specimen’s elongation at fracture or the total strain when the extensometer is removed after offset yield. Next, select a measuring range for the extensometer that meets or exceeds those requirements. If you are using a testing standard, also check the standard for extensometer requirements.

There is a handy Tech Note for reference that you can download here.

How are extensometers interfaced with testing machines?

Most extensometers have either a strain gage bridge or a “high-level” analog output (usually ±10V or 0-10V). Some extensometers use LVDTs, quadrature-output encoders, analog potentiometers, or digital processors that provide measurements as a serial data stream. In any case, the testing machine must have electronics that are suitable for the type of extensometer. For example, electronics for a “strain-gaged extensometer” will need to supply an excitation voltage to the extensometer’s strain gage bridge and will have to amplify its millivolt-level output.

Epsilon can supply whatever connector you need to match your materials testing machine. We can also supply stand-alone electronics for strain-gaged extensometers if you are unable to obtain suitable electronics for an older testing machine.

Learn more on our Compatibility page.

How to specify an extensometer

First, determine what gauge length and measuring range are required for your applications. Often several gauge lengths are required for testing various specimens; additional ‘gauge length adapter kits’ to adjust the gauge length (or additional extensometers) may be necessary to meet all requirements.

Also, your specimens may require several different measuring ranges and, consequently, several extensometers. In most cases, you will get the best data quality when making critical measurements at strain or displacement values greater than 1% of the extensometer’s measuring range. For example, you may get poor data quality when measuring the 0.2% offset yield of a metal specimen using an extensometer with a measuring range of 100% strain. For that application, it is recommended that you use an extensometer with a measuring range of 50% or 25% (or less) instead.

In addition, determine the range of specimen temperatures that you will be testing. Does the extensometer need to be used inside an environmental chamber or cryogenic chamber where the extensometer is at the test temperature?

Lastly, make sure that the testing machine’s electronics can work with the type of extensometer you will be using. For example, a strain-gaged extensometer requires electronics for that type of transducer.

Remember to determine how you will calibrate the extensometer and the testing machine in advance, and how you will verify the accuracy of the extensometer measuring system. Nearly all of Epsilon’s extensometers include a means of electrical calibration (see shunt calibration for strain-gaged extensometers), but you will also want to verify the strain measuring system using a mechanical extensometer calibrator such as Epsilon’s 3590VHR calibrator, or via a calibration service provider. Planning and budgeting for this final step are crucial.

Check out the different models and their applications on the Extensometers Overview page.